| March 17: | What went wrong at the UN? | April 15: | Is Syria next? |

| March 18: | Is this about bin Laden? | April 22: | Is Israel next? |

| March 19: | What does Bush expect to achieve? | April 23: | Where are the human bombs? |

| March 20: | The anti-war protests start | April 29: | My prejudices about Arabs |

| March 21: | There is no Truth | May 2: | Peter finally gets it |

| March 22: | Still obsessed | May 9: | The final proof! |

| March 23: | Horror today versus [?] tomorrow | May 13: | The (evil) empire strikes back! |

| March 24: | My nightmare | May 17: | And again! |

| March 25: | Peter directs the war | May 19: | Depressing news from Israel |

| March 27: | Art to make war bearable | May 21: | Iranian minesweepers |

| March 28: | Stamping out evil | May 22: | Salam Pax is back! |

| March 30: | Suicide bombers | November 28: | Our enemies, the Saudis |

| March 31: | Can democracy succeed in Iraq? | March 8, 2004: | Queen Elizabeth in Yemen |

| April 1: | Perspective from StratFor | May 26, 2004: | Abu Ghraib |

| April 2: | The root cause of Arab hatred | May 27, 2004: | The Arab press |

| April 8: | A bad day for journalists | May 8, 2005: | Thank you and good night |

| April 9: | The fall of Baghdad | ||

| April 10: | The fall of Kirkuk | ||

| April 13: | The hawks preen themselves | ||

| April 14: | Ethnic cleansing in Kirkuk |

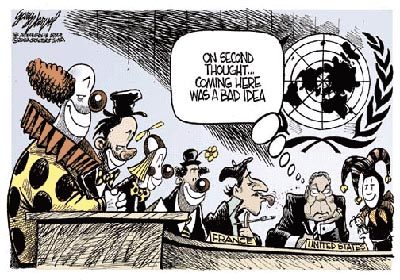

March 17 - War now seems pretty much inevitable - as, I suppose, it has been for months. Some of the serious costs of the war are already apparent in the disarray in the UN.

What happened here? Did the French mislead us and cause the dissent in UN? Our guys complain that the French accepted the principal of forcing Iraq to disarm if Saddam appeared not to cooperate with UN, but then refused to follow through when it was clear that Iraq was just playing hide and seek with the arms inspectors. While we don't know with certainty what Iraq has been up to, Iraq's actions certainly suggest that they have something to hide. Did the French conclude that having the inspectors prying around in Saddam's knickers was enough to prevent him from ever making his weapons effective? That's not an unreasonable thought, but if so, why didn't they explain this to us last fall? Could we have reached an entente cordiale then?

Or did we mislead them about our determination to go to war? Were we so sure that Blix would uncover the smoking gun that would galvanize the UN into action that we weren't prepared for an indeterminate outcome? We end up looking silly by talking for months about the UN as the legitimizing force for addressing the problem and then dismissing them contemptuously in favor of unilateral action. Big mistake - if we knew from the start that we would go to war no matter what, we should have started a long time ago explaining why the US should not have to work through the UN.

Can this blow to internationalism be papered over after the war is over? Or is this a death-blow to the concept of international law? Or was international law always a fiction, as American conservatives have always maintained? Without an international police force that could punish contravention of these laws, how can we expect any kind of international action other than coalitions of the moment? I imagine the UN will survive, but it must always be remembered that the power of talk on the east river will never overpower a genuine perceived need for unilateral action. But I like the fiction of a world order and I would be sad to see it jettisonned in exchange for a return to the overt doctrine of might makes right.

March 18 - I spent much of the day worrying about the Bush doctrine of preemption. Can you really have a world in which potential threats are considered a reasonable cause for a preemptive war? Yes, to a degree - for example, when you see enemy troops massing on your border. But what about a more remote threat? Clearly, the doctrine is unsuitable where you have two potential combatants who are each a potential threat to the other, who will immediately try to anihilate each other (which is perhaps why we didn't pick on North Korea.) Like everything, I suppose, it is a matter of degree. One thing I do know is that we should not overestimate our ability to extrapolate accurately from today's vague threats to future conflicts and loss of life. For many years, we feared the Soviet threat, not without reason, but after 40 years of living with the fear, we suddenly saw it melt away. It seems clear that our policy (and that of the Soviets) of not striking first saved millions of lives.

I am reminded of an experiment described by Dawkins in The Selfish Gene, in which thousands of agents in a computer simulation are given various rules for dealing with other agents near them, and then the process of interaction is simulated over many generations. Pacifists are squished, of course, but the interesting thing is that the very aggressive agents die out, too - generally by spawning too many aggressive children that wipe out everyone in the neighborhood. The most stable rule that evolved to take over most of the territory turned out to be Tit for Tat - a nice, generous rule that never takes first blood but that cannot be attacked with impunity.

What is bin Laden's role in the current conflict? I believe that it is crucial, in the following sense. For some years before September 11, we actually had pretty good information that he was an active and capable enemy of the US, but we were not prepared to make the tough choices to tackle him head on, other than Clinton's one ineffective missile strike. When Bush became President, his initial approach to what he considered to be minor threats was essentially reactive - basically Tit for Tat. After September 11, Bush saw that this reactive mode may have cost us 3,000 lives and billions of dollars. Tit for Tat works well when the impact of any given Tat is not extreme and when the delivery of the Tit is unquestionable. But the world has been changing to the disadvantage of the Tit for Tat strategey, as we get closer to being able to pick up nuclear weapons at the local hardware store and as our enemies become less linked to specific pieces of real estate. Hence, the perceived need to be much more proactive in managing threats that may or may not be able to harm us in the future.

Even when we are able to convince ourselves that a regime poses a huge and tangible threat to us in the future, any action we take is bound to be perceived as unfair and to provoke resentment among other nations who begin to see that they are all vassals of the one dominant power. Is this what happened to the Roman Empire? What were the Goths up to, anyway? Freedom fighters? Or just resentful of Rome's wealth and power and happy enough to destroy it? Note to self: check out the fall of the Roman empire.

March 19 - Found myself trying to understand the Bush POV. The war is concluded with dispatch, with mass defections of Iraqi soldiers in the face of overwhelming US power. The anti-war feelings dissipate - people will feel foolish after concluding that US and (most of the) Iraqis are on the same side. We foster a secular democratic state which serves as a model for the rest of the Arab world. Political stability in the Gulf is improved, fostering more efficient trade. Standards of living rise in the Arab world and the Arab man on the street joyfully embraces Western values. Kind of like the White Man's Burden, as shouldered by colonial Britain.

Are these reasonable prospects? I don't have any real knowledge of comparative military capabilities but it is certainly possible that we might conclude the hot war quickly and without large civilian casualties, as we did in 1991. If Bush doesn't have a lot of confidence of this, he really hasn't done his homework. It also is possible that the majority of Iraqis will conclude some months after the war that they are better off without Saddam, despite the destruction and casualties of the war, and that the prospect of democracy and pluralism is enticing. On the other hand, not everyone will feel that way - particularly religious leaders who see pluralism as the enemy and radicals who are unshakably anti-American. And forging a genuine balance of interests between Kurds, the traditional Sunni power base and the Shiites is going to be harder than getting peace in Afghanistan. (How about a national pow-wow, on the order of the one in Afghanistan?) But one must assume that the government has got some preliminary indications of who will control these various groups after the war and whether or not a consensus can be obtained between them.

So the dangers of screwing things up in Iraq are obvious enough, and I have enough confidence that our govenment has made a reasonable assessment of them and taken reasonable precautions to contain them. More dangerous, however, might be other, less tangible consequences on world order, religious intolerance and so on. I worry about these things a lot, without really having a clue what drives them. Does the government understand them better than I? I'm not sure that anyone really does.

Conclusion: I really do believe that the US leadership is managing the obvious high-probability events that could be disastrous to the US. At the same time, the great imponderables are worrying the hell out of me.

March 20 - I spend the entire day being very distracted. First, the shooting war starts - we try to destroy the Iraqi leadership and troops enter southern Iraq. Protests erupt in the US and around the world. I find it impossible to work - instead, I compulsively watch TV, listen to the radio on the Net, play Freecell. I am astounded by the arrogance of the anti-war demonstrators - how can high-school students really think that they understand the shadowy circumstances of the current situation better than I do, when I don't think I understand it at all? Perhaps some are opposed to all war, any time, so that they are not even trying to judge the particular circumstances of this war. Such extreme forms of pacifism may not be characterized as arrogant, but I think that few people are truly willing to accept the fate of the meek facing a Saddam-like antagonist - I know I'm not.

Much of the anti-war rhetoric seems to be directed at Bush's political language for justifying the war. This seems naive - the political language used to justify any act of govenment is always excruciating. (Coalition of the Willing - yikes!) Yes, the terrorism connection is tenuous and yes, the immediate level of threat to the US is low. But, guys, we must move beyond the language that politicians use to examine what is truly at stake. Let's by all means discuss the merits of preemption and try to set reasonable guidelines on when it should be used. People of good will will differ over where the line should be drawn, but that's what the ballot-box is for. I find I react very negatively to the self-righteousness of the demonstrators who are angrily declaiming that they will keep protesting until their voices are heard. Don't you believe in the democratic system? Once it has been established that pro-war sentiment overwhelms anti-war sentiment by 3 to 1, shouldn't you go home? Wouldn't there be something profoundly wrong with a system that allowed street protests by a minority of Americans to have a disproportionate influence on American policy? Who would be next on the streets? The Klan?

Now I am ranting like some reincarnation of General Westmoreland. The truth is that I am by constitution a pacifist. I feel the knee-jerk appeal of resisting the call to war as strongly as anyone. When the US government focused its ire on the Taliban regime in Afghanistan after September 11, I started hoping that we'd fink out of a real engagement there. What about the danger of a Vietnam-style morass? Might we share the fate of the Soviet Union? What about the imponderable effects on world opinion? (See my scribblings at the time in Assault on Washington.) When the smoke cleared, it is clear that my worries could be written off to a combination of a lack of knowledge about the military situation and perhaps a testosterone deficiency. Now that nice Hamid Karzai is running the place (well, running Kabul, at least), the terrorist training camps are gone and I don't hear any complaints about how the evil US is oppressing the poor Afghan Muslims.

March 21 - Today is the first day of spring, and I am still glued to the TV and the radio. We see pictures of US and British forces moving swiftly into Iraq and columns of surrendered Iraqi soldiers trudging down the road with their hands on their heads. The Iraqis deny that their soldiers have been surrendering, that US has penetrated into the country.

As in all such situations, I am amazed that There Is No Truth. We like to think that facts exist indisputably outside us all but that we all view them fuzzily, as through a glass darkly, so that we can easily mistake one thing for something else. But others can help us to wipe off that glass and make the Truth inescapable to us all. In truth(?), though, facts are an invention of people and they are marshalled only in support of whatever we wish to believe. Did Americans stand on the moon in 1969? A lot of people believe that it was a crude Hollywood trick that Americans were happy to believe because it was convenient to our national pride. Did the Jews really destroy the Twin Towers? It must take quite an effort of will to believe that one, but millions of people apparently do. We have direct first-hand knowledge of so little that we need a gigantic filtering apparatus to help us decide what hearsay to believe. That filter probably is somewhat responsive to facts and reason, since it is too important a part of our evolutionary apparatus to ignore things that may be crucial for our survival, but it is a cultural artifact and, like the Titanic, it has a huge momentum of its own. The conspiracy theory makes pretty much anything believable - V.S. Naipaul reports that many Iranians believe that the West secretly conspired with Khomeini to install him as leader of Iran to punish the people for overthrowing the Shah. Wow!

(Random digression: I think the one recent news item to compell Arab belief in American technical wizardry was ironically the destruction of the Columbia space shuttle, since they couldn't resist an opportunity to exult at the death of an Israeli along with the regular American crew. But if the destruction was real, then you've gotta admit that we really do have space shuttles and a space station.)

It is tempting to believe that the existence of a free press makes it harder for radically different versions of the Truth to co-exist. At very least, I believe the converse - that any government information monopoly is inherently unreliable and, in the absence of an independent press, any version of the Truth is as believable as any other. But I believe that a huge cultural adjustment needs to take place before Western filters and Arab filters produce similar Truths. There is little chance that the "Arab street" will be turned around by a favorable outcome of the Iraqi war, no matter how much Iraq's Hamid Karzai (whoever he may be) tells the world that the Iraqi people are grateful to the Americans for freeing them from Saddam's tyranny. (Well, of course he is only saying that because he is a vile American puppet...) The pictures from al Jazeera all show babies with hideous wounds from Coalition bombs, while we are watching smiling Iraqis greeting their liberators. I fear that continuing resistance to a US presence will make reconstruction very difficult and present plenty of opportunities for Arabs to see yet more evidence of the US oppressive colonialist spirit.

Oil prices plummet and the stock market soars as consensus develops that the war will be short. The big bombardment starts and I cringe at the thought of how easily the peace can be lost here and now by inflicting massive civillian casualties and turning the Iraqi populus permanently against us.

March 22 - A lovely sunny day, which I still spend in my office, listening to war news on the BBC on the Internet and furiously penning these notes. But I end up mostly editing my thoughts from previous days.

March 23 - And yet another sunny day. The US shoots down a British jet. A Coalition plane goes down over Baghdad. A Muslim US sergeant stages a grenade attack on his officers in Kuwait, killing one of them. Iraq parades some dead and wounded US POWs on TV. None of these things are death-blows to the campaign or even material to the progress of the attack, but my pacifist bones ache prodigiously. Once again, I remember the Afghan campaign, and the anguish surrounding the accidental bombing of Canadian forces and the repeated visits of reporters to the remnants of houses of Afghan civilians, targeted in error by American bombs.

Now that the hot war in Afghanistan is well off the front pages, however, it's hard to remember more than the fact that we prevailed against the Taliban and that my fears at the time now seem way overblown. After the fact, when these images are no longer on the TV screen, we can perform the grim calculus of trading off the actual death and destruction of war against the virtual horrors avoided. For the moment, however, the actual visible death and destruction in Iraq has a visceral power that no description of what might have been can ever have, no matter how convincingly argued or graphically described.

March 24 - Here is my main nightmare. When I permit myself to think of a successful conclusion of the hot war, I segue into worrying about how we put a new nation together, based on democratic and humane values. Maybe it ends well - we really do achieve these goals. But, being such a worrier, I think back to Vietnam, in which we tried to support an alternative (please - any alternative!) to a communist regime. We threw tons of money at it and a million-man army to suppress the communists and ended up abandoning the country in disarray, with the communists nipping at our heels. In the Viet Cong, we faced an enemy with a very limited military capability but which was able to bog us down until our will to fight was gone.

But of course there is a more modern analogy which is even more chilling - Israel trying to control the occupied territories. Surely there will be (millions of) those in the Arab world who are quite unsurprised to see us in exactly the same role as the Israelis and who will be quite willing to apply the same measures that have been successful in wreaking havoc on the Israeli economy and morale. Guerilla fighters slip into the country from Syria and Iran and Saudi Arabia to harass us and penalize the Iraqi population for cooperating with our attempts to lead them westward. Muslim teenagers stand in line for the privilege of blowing themselves up, to ensure that we can't relax or treat the Iraqis as friends. We find that this village has been sheltering fighters and so we move in with the bulldozers to flatten it to teach the other villages a lesson. Arab guerillas hide among the civilians, so our efforts to root them out leads to the accidental deaths of more children which provoke tearful Iraqi vows of revenge. The cycle of hatred spins ever faster.

How does this story end? Not well for anyone. Ever more casualties and bitterness on both sides. More Al-Qaeda attacks in the US. The legend of the evil US is now supported by plenty of very specific stories of perfidy and horror, rather than being linked in a rather vague way to an immoral and seductive culture with too much military and economic might. (Perhaps it will at least get the Arabs to forget the crusades, for God's sake, and feel bitter about something a little more relevant to modern life.)

But we also have to ask how the other story ends - the one in which we decide not to invade Iraq. Maybe nothing - Saddam is run over by a bus and a more enlightened leader emerges who charts a course leading eventually to democracy. But then maybe he isn't run over by a bus but develop nukes and then provides them to terrorist groups. No more Israel. No more New York City. The value of my real estate plummets.

The stock market plummets today, too, as the consensus swings to fearing a more prolonged hot war. And so it goes...

March 25 - I wonder if the psy-ops campaign has been lost. At the beginning of the war, we made all of these portentous remarks about the Mother of All Bombardments. We leafleted the countryside with instructions on how to surrender to the unimaginable might of the US. And then we relied on a lightning strike up to Baghdad to show our super-human capabilities.

But, much to my shock and awe, this does not seem to have produced the demoralization we were looking for. By moving so fast, we have exposed support troops to guerilla attacks which have occasionally been successful in producing US casualties and captives. Yesterday, the Iraqis managed to shoot down a US helicopter; ironically, this gave us our first convincing pictures of smiling Iraqis dancing in the streets. And once we have bluffed and lost, and our foe gets a sudden heady realization that Americans are just made of flesh and blood, we may be worse off than if we had not bluffed at all but just trudged slowly into Iraq, pacifying each town as we went.

God! I can't believe I am giving advice on how to fight the war! And me hiding under my desk in Larchmont!!

March 27 - Skipped a day yesterday, which is actually good news for me - I guess I'm getting a little less obsessed with the war. Not that the war news was any more fun - the big item was the Iraqis claiming that a missile strike flattened a civilian area in Baghdad, causing heavy casualties and accompanied by TV pictures on al Jazzera of weeping relatives waving severed body parts in the air and vowing revenge on the US - but I found that I was able to distance myself a bit more from it, just watching a few snatches of TV during the day and keeping the radio off. Of course, American TV declined to show the severed limbs, but there is something strange about the US broadcasters shying prudishly away from the nastiness that appears on al Jazzera at the same time that they are busy sating the public's appetite for reality TV shows. What is war but the ultimate reality show? Hey, make up your minds, guys!

There's an nice op-ed piece in the Times today by an Iranian, Azar Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Tehran, who taught literature classes in Tehran during the Iran/Iraq war while Saddam was busy lobbing in shells with chemical warheads. She comments on the importance of seeking out beauty and poetry rather than dwelling on the horrors of the moment.

March 28 - Another beautiful day in Larchmont. It always seems creepy that things can be so serene when people are fighting for their lives in Iraq. I remember the same feeling on September 11, which was equally sunny and peaceful in Larchmont at the same time that downtown New York was in ruins. On the other hand, people are always fighting for their lives somewhere in the world and it would be a shame not to enjoy the sunshine where you can.

You hear Bush and the other US leaders speak about the war on TV in terms of the neccessity of overthrowing evil. I don't think there's much need to worry that the US is becoming driven by purely moral principles in such matters, but it does make it difficult to know what the country's leadership is truly trying to achieve. One possibility, as outlined above on March 19, is the idea of trying to build an Arab state in which western values are respected. Although this sounds ludicrous right now, while the bombs are raining down on Baghdad, it might be a reasonable objective over the longer term - think Germany after WWII. Certainly, this seems to be Blair's main focus.

The other main candidate is the preemption argument - that we could see the inevitability of Saddam's acquiring Weapons of Mass Destruction (or WMD - what a ridiculous acronym!) and using them against us by making them available to an anti-American terrorist group like al Qaeda that is not tied to Iraq or any particular nation. This is a much more horrifying argument and I hope that it turns out to be crap. Pakistan and North Korea already have nuclear weapons and I imagine that the main effect of the war so far is to make them more likely rather than less likely to use them in this way. Iran is probably only a few years from gaining nuclear weapons, and they are already active sponsors of terrorism against Israel. Thus, if the notion of unfriendly governments making nukes available to terrorists to use against its enemies is not totally absurd, the cat seems to be pretty much out of the bag. If so, perhaps we would have done better to spend our time kissing our tushies goodbye instead of embarking on this venture.

Is there any hope of living the peaceful life in such a world? The idea of every little country having access to nuclear weapons (or other WMD) and being able to use them more or less invisibly against its enemies is truly horrifying. Tit for Tat (or MAD) doesn't work if you can't be sure who is responsible for destroying your major cities. I guess the US could announce in advance that we'll smash all countries with governments that are even slightly hostile to us if we are so attacked, but such a strategem could stimulate game-playing behavior in which country A wants to destroy country B, which is incidentally a bit hostile to the US, and achieves it by planting a small nuclear weapon in a shipping container bound for New York! It also leads to a horrifyingly large loss of life.

I think we need to marshall all the ideas of all of the clever game theorists to devise a stable world order. Perhaps this military campaign is what the game theorists came up with? You cannot afford to allow any nation to possess weapons of this kind unless their culture clearly imposes some strict constraints on their use. Most nuclear nations can only conceive of using such weapons as a last resort. But any culture lacking that restraint - perhaps the Arab nations? - must never be allowed to obtain them. (Perhaps we are actually a lot more comfortable with the North Koreans having nukes, for that reason?) At the same time, you can't really state this clearly as a national objective, since it would cement the notion of the Arabs as second-class citizens of the world. Hence the big push to rid the world of evil.

March 30 - Another crummy day in Larchmont - chilly, rainy, with some sleet and snow. The war no longer presents breath-taking feats of military brilliance but just grinds on and the politicians start to prepare people for a campaign in the months, not days. I manage to bring my head around to deal with business as usual, pretty much. I am doing some work and only permitting myself a minimum amount of time worrying about the war. The first Palestinian-style terrorist act - a suicide car bomber - kills four US soldiers - ça commence.

I have some mixed feelings about these suicide bombers. First, I try to put myself in the bomber's place. Man, I can't imagine myself having the guts to do that! Must take a magnificent act of will. If I were part of a unit fighting the enemy and about to be overrun by enemy troops, and one member of the unit volunteers to stay put and hold up the attackers, thereby allowing the rest to escape, I would think very highly of that person's willingness to accept almost certain death for the sake of his comrades and the ultimate success of the war. Think Bruce Willis in Armageddon. I can imagine myself taking on a somewhat greater risk of death for the sake of my comrades, although assuming a somewhat higher risk of death seems different from honest-to-goodness suicide.

But the part that really bothers me about the suicide bomber is that he might consider that he is coming out ahead by destroying himself, thereby being seated at the right hand of Allah and being given 72 virgins and all that twaddle. Such a strong belief in the afterlife and the Islamic reward system captures the awesome power that I fear and loathe the most about religion. All nations preach the virtues of being willing to sacrifice oneself on the battlefield in order to defend the motherland, but the "holy martyr" approach of the Arabs appear to have taken it to such an extreme that it threatens to undermine normal principals of equilibrium among nations. Imagine a country that considers a devastating nuclear strike against its enemy as desirable for two reasons - first, it destroys large numbers of infidels, and, second, the ferocious retaliation it provokes merely sends the faithful to unimaginable bliss at the side of Allah. This is perhaps the underlying cause of the war in Iraq and ultimately may lead to a huge nuclear holocaust in which the entire middle east will become a smoking radioactive pit. (And maybe Larchmont, too, although I daren't say so for fear of depressing real estate values.)

A piece in the Times (Who wants to be a martyr?) by Scott Atran, argues that Islamic martyrs are generally well educated and well-adjusted, not foaming-at-the-mouth lunatics or despondent peasants who have nothing to lose.

March 31 - Read some thought-provoking pieces that Jorge sent over on whether we should expect a post-war experiment in democratization to be successful or not. The main candidates are: NO - the notion of democracy is too foreign to the traditions of the Arab world, and the fact that it was imposed by the US would in any case make it unacceptable; YES - it may seem radical, but what else is there, other than a continuation of oligarchs and dictators, which surely the Iraqis are fed up with? My own reservation is that the only group with any real popular support might turn out to be the radical Islamists, so we would get dreadfully embarrassed and explain that we didn't really mean democracy, we meant secular democracy. The Arabs would conclude that we were never serious about democracy, just about stealing their oil, and would chase us out of their neighborhood. Then they would get back to working on the WMD...

One of the authors put forth the example of Japan, a highly militarized, anti-western autocracy before the war, transformed into a western-friendly democracy over less than a decade following the war. The comparison actually goes much further - the kamikaze fighters, willing to kill themselves for the sake of the emperor aren't that far from the suicide bombers willing to blow themselves up for Allah. Where did the spirit of the kamikazes go? Into building the perfect portable music player? I think we need to analyze this process carefully so we can channel all that Arab fervor into something equally useful.

I just read an interesting paper on the kamikazes by Mako Sasaki, published in the Concorde Review. ( Who Became Kamikaze Pilots and How did they Feel Towards their Suicide Mission? ) She concludes that the pilots were basically average Japanese boys in their late teens - not extremely religious or patriotic. They seem to have been motivated in part by religious factors, although not exclusively after-life considerations. At that stage in the war, Japan had few qualified pilots and little hope of prevailling against better qualified Allied pilots, but the Japanese command concluded that the one way in which they outnumbered the Allies was in numbers of young men who were prepared to die rather than face dishonor.

April 1 - Just saw a few flakes of snow - in April, no less! Is Allah displeased with us?

Here is some interesting analysis from StratFor:

Washington's decision to redefine the conflict was driven by the ineffectiveness of this response. The goal has been to compel nations to crack down on citizens are enabling al Qaeda -- financially, through supplying infrastructure, intelligence and so on. Many governments, like that of Saudi Arabia, had no inclination to do so because the internal political consequences were too dangerous and the threat from the United States too distant and abstract. The U.S. strategy, therefore, was to position itself in such a way that Washington could readjust these calculations -- increasing cooperation and decreasing al Qaeda's ability to operate.

Invading Iraq was a piece of this strategy. Iraq, the most strategic country in the region, would provide a base of operations from which to pressure countries like Syria, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Iraq was a piece of the solution, but far from the solution as a whole. Nevertheless, the conquest and occupation of Iraq would be at once a critical stepping-stone, a campaign in a much longer war and a proof of concept for dealing with al Qaeda.

Copyright 2003 Strategic Forecasting LLC. All rights reserved.

In other words, to win the war against terrorism, we need the cooperation of Arab states who have historically relied on buying off their religious extremists in return for a promise that they will make mischief elsewhere. Since September 11, this is no longer acceptable to us. We occupy Iraq and suddenly we are in their faces, reminding them of what happens if you fail to placate Washington. Implied in this analyisis is that ultimately it may not matter what the Iraqi people think of us so long as the other Arab leaders appreciate our ability to project power into the middle east and agree to crack down on the forces that fuel the terrorists.

April 2 - A grey, chilly day in Larchmont. Iraqi brigades of Republican Guards line up outside Baghdad to take their punishment from a torrent of bombs and missiles while US troops take a rest. The stock market surges on the expectation that the air attack will decimate the Guard, so that they can present no further obstacle to the advance of the US Marines into Baghdad, although what happens after that is anyone's guess.

My current understanding of how the US is pursuing the war is basically along the lines of the StratFor quote from yesterday.

I think that these principles make a certain amount of sense. Looking back on the 90ies, we were in the unenviable position of being in a conflict with al Qaeda without feeling like we could really take the initiative. All we did was respond to increasingly damaging attacks by taking increased security precautions. Our slowness to respond to the threat of al Qaeda reflected our inability to see it as a symptom of such a broad hatred by so much of the Arab world. Hadn't we protected the Kuwaitis in 1991? Hadn't we taken up arms against the Serbs to protect the Muslims in Bosnia? Such a defensive posture could only end up with a disaster such as occurred on September 11, 2001. This was our wake-up call - something is going on in Arabia, and perhaps to a lesser extent in other Muslim nations, that is creating a fervent hatred of the US that we have not seen before.

As described yesterday, even taking the field against al Qaeda and thrashing them in Afghanistan does not win the war on terror. There is no success in the war against terror without addressing the root causes of that hatred. If we don't succeed in heading it off somehow, we will just face ten more bin Ladens. My main problem is that I'm not sure I really understand where the hatred comes from, although I do know that the explanations provided by the Arab in the street - such as our supposed tilt in favor of the Israelis and against the Palestinians - are superficial and that there is little we could gain even if we nuked Tel Aviv.

So what other candidates do we have? The first and most commonly cited is Islamic fundamentalism. The problem with this as an explanation is that it seems more like a symptom than the true cause. Why should religious fundamentalism create these feelings of hatred? Why does fundamentalism seem to be on such a roll in the Arab world? It does seem to be true that anti-American hatred is nurtured by these groups, and that a particular finger has been pointed at the austere Saudi-sponsored Wahabi version of Islam which has spawned bin Laden and the majority of the September 11 hijackers. But it is not by itself a satisfactory explanation of the changes that have occurred in the Arab perspective on the west over the past decade.

The other main candidate is western support of governments that are seen as corrupt and oppressive. This explanation at least points to a connection between the US and the Arab on the street, although it seems pretty tenuous to most westerners. It is true that many of the Arab governments may be seen to have failed their citizens on two counts - first, they have failed to create western-style wealth for the average Arab, who sees himself slipping further and further behind western living standards. To take comfort for this failure, Arabs retreat further into a religion which tells them that they shouldn't have looked to the west in the first place because western culture is decadent and immoral. So far so good, but their governments see religious fundamentalism as a threat to secular government and feel obliged to suppress it. Thus the Arabs' convenient retreat into fundamentalism to avoid recriminations of failure in the arena of global economics is cut off by their governments' fear of Islamic revolution. The resulting frustration needs an outlet - and we're it, whether it is because we are seen to have provided support to their governments in suppressing fundamentalism or because we are the source of the economic competition and cultural decadence that caused the problem in the first place.

Then there's a third possibility - the Gulf war of 1991, which shouldn't be ignored since the timing coincides nicely with the rise of bin Laden. In some Arab circles, the war was doubtless interpreted as a humiliating blow to Arab self-esteem, despite the fact that we were coming to the aid of an Arab nation, since we showed our vastly superior military prowess. This evokes ancestral memories of the crusades and stimulates an Arab movement determined to show that their power is equal to that of the west, albeit channelled though terrorism rather than conventional (i.e. western-style) warfare. It also fuelled a major funding for fundamentalist causes, as described in this rant by Salam Pax, who lives in Baghdad and posts a daily weblog.

It only happened after the Gulf War. I think it was Cheney or Albright who said they will bomb Iraq back to the stone age, well you did. Iraqis have never accepted religious extremism in their lives. They still don’t. Wahabis in their short dishdasha are still looked upon as sheep who have strayed from the herd. But they are spreading. The combination of poverty/no work/low self esteem and the bitterness of seeing people who rose to riches and power without any real merit but having the right family name or connection shook the whole social fabric. Situations which would have been unacceptable in the past are being tolerated today.

They call it “al hamla al imania – the religious campaign” of course it was supported by the government, pumping them with words like “poor in this life, rich in heaven” kept the people quiet. Or the other side of the coin is getting paid by Wahabi organizations. Come pray and get paid, no joke, dead serious. If the government can’t give you a job run to the nearest mosque and they will pay and support you. This never happened before, it is outrageous. But what are people supposed to do? thir government is denied funds to pay proper wages and what they get is funneled into their pockets. So please stop telling me about the fundis, never knew what they are never would have seen them in my streets. [END OF RANT]

Now, given these various possible explanations of Arab hatred, can we expect that things will improve once the war against Saddam is over? As the progress of the war inevitably rubs Arab noses in their military inferiority, it seems unlikely to be a success, per explanation #3. We have not only demonstrated our might, but this time we have done it by invasion, not by coming to the help of an Arab ally. Crusaders, beware! Score one against the war.

As far as solving the Arab failure trap goes, the war could ultimately lift the Iraqis out of it. The key would be to succeed in cobbling together a workable government that: (i) eschews WMD, (ii) proceeds on somewhat democratic principles, (iii) is recognized in Iraq as legitimate (i.e. not simply imposed on them by the US), and (iv) results in material prosperity. Is that likely? I am in fact more optimistic today that the situation in Iraq will achieve these goals - today, there was a news report that a prominent Shiite cleric had issued a fatwa to the effect that Iraqis should let the Coalition troops complete their mission, and Coalition forces are already probing Baghdad. And while I expect persistent hostility from Sunni Arab Iraqis whose ruling elite will have been displaced, I believe that the net effect on Iraqi majority opinion will ultimately be positive.

But the troublesome part is the final act - the coup de grace against the root cause of terrorism throughout the Arab world. It is possible that the example of a prosperous and nonradical Iraq might serve as an example to all Arabs who might see this as a worthy goal for them. But why? According to the failure trap, per explanation #2 above, western materialism has failed them and it would seem to take a lot of faith for the Arabs to hitch their wagon back to that fallen star.

So what exactly are we planning to insist that the Saudi and Egytian governments do that will transform Arab culture into one that has more tolerance for the west? The most tempting but also dangerous and potentially counter-productive thing they could do might well be to apply more pressure on the fundamentalists, which would just turn up the heat under the pressure cooker. You can be sure that Prince al Saud would whisper to the congregation as he is leading their mullah off to jail: "The Americans made me do it!" Our ability to twist the Saudi rulers' arms is of no use unless we have a clear idea of how they can affect Arab culture to our advantage.

So what might work? I think it is likely that there will be a subtler attack on fundamentalism via its funding, particularly in Saudi Arabia. This might avoid the impression that the US is interfering in the affairs of Islam, but I'm not sure how much power it would have to affect the culture. What else is there? My belief is that the only way in which Arabs will ultimately be able to get out of the trap they are in is by feeling that they have taken responsibility for their own destiny. Unfortunately, in the short run, this probably means that the Islamic fundamentalists must be allowed more freedom to preach against modernism and western values. But the austere life is not what most people want, and a few years of the religious police will likely give rise to a movement back towards a more western perspective, as we are seeing in Iran. Only then, when it is springing from the hearts of the Arab people, is it likely to lead to an end of Arab hatred. The key question for me is: when this finally occurs, will Larchmont still exist, or will it have been reduced to rubble by a new bin Laden? And the answer is: dunno. But I'm not sure that there are other obvious alternatives to the war that would give me any greater comfort.

Copyright © 2002 by Peter Lloyd-Davies. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement.